Barber paradox

- This article is about a paradox of self-reference. For an unrelated paradox in the theory of logical conditionals with a similar name, introduced by Lewis Carroll, see the Barbershop paradox.

The Barber paradox is a puzzle derived from Russell's paradox. It was used by Bertrand Russell himself as an illustration of the paradox, though he attributes it to an unnamed person who suggested it to him.[1] It shows that an apparently plausible scenario is logically impossible.

Contents |

The Paradox

Suppose there is a town with just one male barber. In this town, every man keeps himself clean-shaven by doing exactly one of two things:

- Shaving himself, or

- going to the barber.

Another way to state this is:

- The barber shaves only those men in town who do not shave themselves.

All this seems perfectly logical, until we pose the paradoxical question:

- Who shaves the barber?

This question results in a paradox because, according to the statement above, he can either be shaven by:

- himself, or

- the barber (which happens to be himself).

However, none of these possibilities are valid! This is because:

- If the barber does shave himself, then the barber (himself) must not shave himself.

- If the barber does not shave himself, then the barber (himself) must shave himself.

History

This paradox is often attributed to Bertrand Russell (e.g., by Martin Gardner in Aha!). It was suggested to him as an alternate form of Russell's paradox,[1] which he had devised to show that set theory as it was used by Georg Cantor and Gottlob Frege contained contradictions. However, Russell denied that the Barber's paradox was an instance of his own:

That contradiction [Russell's paradox] is extremely interesting. You can modify its form; some forms of modification are valid and some are not. I once had a form suggested to me which was not valid, namely the question whether the barber shaves himself or not. You can define the barber as "one who shaves all those, and those only, who do not shave themselves." The question is, does the barber shave himself? In this form the contradiction is not very difficult to solve. But in our previous form I think it is clear that you can only get around it by observing that the whole question whether a class is or is not a member of itself is nonsense, i.e. that no class either is or is not a member of itself, and that it is not even true to say that, because the whole form of words is just noise without meaning.

— Bertrand Russell, The Philosophy of Logical Atomism

This point is elaborated further under Applied versions of Russell's paradox.

In Prolog

In Prolog, one aspect of the Barber paradox can be expressed by a self-referencing clause:

- shaves(barber, X) :- male(X), not shaves(X,X).

- male(barber).

where negation as failure is assumed. If we apply the stratification test known from Datalog, the predicate shaves is exposed as unstratifiable since it is defined recursively over its negation.

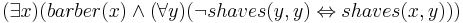

In first-order logic

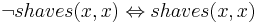

This sentence is unsatisfiable (a contradiction) because of the universal quantifier. The universal quantifier y will include every single element in the domain, including our infamous barber x. So when the value x is assigned to y, the sentence can be rewritten to  , which simplifies to

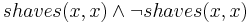

, which simplifies to  , a contradiction.

, a contradiction.

In literature

In his book Alice in Puzzleland, the logician Raymond Smullyan had the character Humpty Dumpty explain the apparent paradox to Alice. Smullyan argues that the paradox is akin to the statement "I know a man who is both five feet tall and six feet tall," in effect claiming that the "paradox" is merely a contradiction, not a true paradox at all, as the two axioms above are mutually exclusive.

A paradox is supposed to arise from plausible and apparently consistent statements; Smullyan suggests that the "rule" the barber is supposed to be following is too absurd to seem plausible.

The paradox is also mentioned several times in David Foster Wallace's first novel, The Broom of the System.

Non-paradoxical variations

A modified version of the Barber paradox is frequently encountered in the form of a brainteaser puzzle or joke. The joke is phrased nearly identically to the standard paradox, but omitting a detail that allows an answer to escape the paradox entirely. For example, the puzzle can be stated as occurring in a small town whose barber claims: I shave all and only the men in our town who do not shave themselves. This version omits the sex of the barber, so a simple solution is that the barber is a woman. The barber's claim applies to only "men in our town," so there is no paradox if the barber is a woman (or a gorilla, or a child, or a man from some other town--or anything other than a "man in our town"). Such a variation is not considered to be a paradox at all: the true Barber paradox requires the contradiction arising from the situation where the barber's claim applies to himself.

Notice that the paradox still occurs if we claim that the barber is a man in our town with a beard. In this case, the barber does not shave himself (because he has a beard); but then according to his claim (that he shaves all men who do not shave themselves), he must shave himself.

In a similar way, the paradox still occurs if the barber is a man in our town who cannot grow a beard. Once again, he does not shave himself (because he has no hair on his face), but that implies that he does shave himself.

In music

- Chip Hop (rap) artist MC Plus+ refers to the Barber paradox in his song "Man Vs Machine" from the album Chip Hop. He uses it to defeat his own fictional AI opponent, Max Flow, in a rap-battle.

See also

References

- ^ a b The Philosophy of Logical Atomism, reprinted in The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, 1914-19, Vol 8., p. 228

External links

- Proposition of the Barber's Paradox

- Joyce, Helen. "Mathematical mysteries: The Barber's Paradox." Plus, May 2002.

- Edsger Dijkstra's take on the problem